In March, MoDiP was invited by the BPF to provide a short series of webinars about classic design inspired by objects in the MoDiP collection.

One of these talks was inspired by the EKCO A22, by E K Cole Ltd. This radio was designed by Wells Coates and manufactured in 1945 making it one of the last of a series of circular radios – the first being the AD65 designed in 1932 and manufactured in 1934.

In 1924 Eric Kirkham Cole, together with his future wife, Muriel Bradshaw, set up a business making radio sets in Southend-on-Sea, Essex. They joined forces with William Streatfield Verrels to form a private company in 1926 producing battery eliminators making it possible to power radios through mains electricity rather than relying on batteries.

In the 1930s, the company concentrated on making mains powered radios rather than the battery eliminators which were becoming obsolete. They initially had their Bakelite cases made by AEG in Germany, but spurred on by the introduction of high import duties they established their own Bakelite moulding shop. AEG helped them set up this up.

After slumping sales and a disastrous factory fire in 1932, in which all the designs for the new season’s radios were destroyed, the company looked to key designers and architects of the day, such as Serge Chermayeff and Wells Coates to design cabinets for them and help rescue the firm.

To demonstrate the importance of the Wells Coates radios, this artwork called ‘Our Eric’ was put up in October 2020. It is located in EKCO Park housing estate, where the factory once stood. His suit is made up of a mosaic of 182 photographs showing the social history of EKCO, and he is stood on the AD65. The top image shows a line of women hand finishing the cases for the same radio.

Wells Coates was born in Japan in 1895 and died in Canada in 1958. One of his best-known architectural works is the Isokon flats in London, shown on the left.

He studied engineering to PhD level and was interested in Modernist design – he embraced Le Corbusier’s architectural mantra that a ‘house is a machine for living in’ and as such should fulfil a specific function.

He designed a studio for the BBC in 1930, part of which included a counterbalanced microphone that was ceiling mounted, could be easily moved around, and stay as it was positioned. In the slide below, he is pictured with two of his EKCO designs, the Radiotime from 1947, which allowed you to set the time you wanted the radio to come on and switch off for the very first time, and the Princess Potable from 1948, which utilised much smaller valves and batteries allowing a much smaller radio to created.

Radios are socially and culturally really important. Wireless sets, are said to be the first pieces of electrical equipment to be owned on a mass scale in Britain, they are described as wireless sets as the receiver and speaker were often separate to avoid vibration effecting the sound. This example is the Burndept IV Wireless receiver from 1924.

In 1922, when broadcasting began, there were 36,000 licences for receivers, this went up to 4.3 million by 1931, and then in 1939 there were 9 million licences.

There are reported to be three distinct stages in the appearance of wireless sets:

The first stage sits in the years immediately after broadcasting began. Here the technology is the most important factor. Consumers and manufacturers were focused on innovation and the latest technical improvements. The look of the piece was less important.

In the 1920s, wireless-making became a boom industry – hire purchase meant that even relatively poor people could buy radio sets. The industry grew very fast, but innovation started to slow down by 1929. The technology between one company’s set and another was not that different.

The next stage in radio development, saw the focus move from the technology to the external look of the device.

But what should a radio cabinet look like? There was no precedent, nothing to compare it to other than furniture. So, to hide the apparatus many radio manufacturers outsourced the cases of their radios to cabinet makers who created things that resembled other pieces of furniture. At the time there were complaints that radios were not distinguishable from other pieces of furniture in the house with reports that guests mistook the radio for the cocktail cabinet. The bottom two examples on this slide show a large cocktail style cabinet and a radio set into an armchair.

It might be said that the technology of radio could be quite strange and disturbing, so to have something that seemed comfortable and familiar helped to assimilate the unfamiliar into people’s homes. Radios eventually become the focal point in the room in the same way that the TV might be today.

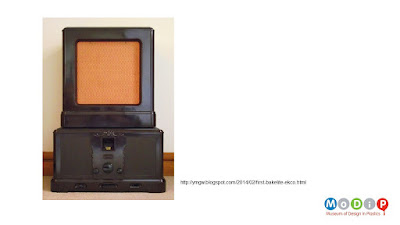

And so…. some companies including Murphy and Pye focused on manufacturing good quality sets in a medium price range, with recognisably modern cabinetry, they fit in with the style of the day, being fashionably Art Deco, but are made of wood.The first EKCO brand Bakelite-cased radios were the 312 and the 313, both released in 1930. This is the 313, which still has the look of a wooden cabinet and was available in colourways such as Mahogany, and medium oak. This piece was being sold in wood like colourways and was designed by a furniture maker, but it marks the beginning of the third stage of radio case design.

By using phenol formaldehyde E K Cole were bucking the trend, they did however feel that it was not using the material to its full potential. Although technology had slowed, radio was still seen culturally as a symbol of social change and technical progress.

E K Cole turned to designers more associated with the Modern Movement to achieve something more appropriate to the material. However, what this stepping stone design did was make way for the more radical designs that were to follow, which may have been too radical for the buying public and would not have been the success they proved to be without this piece in between.

As I have said, the radio case could become shape, it did not have a long history unlike something like a kettle for example which has been around in some form or another for hundreds of years – we know it should have a handle, a lid, and a pouring spout.

Alongside radio cases having no intrinsic shape, we know that plastics are the same. They can be made into any shape, have any texture, and now any colour. By using phenol formaldehyde, the radio cases we are talking about have a restricted colour palette.

The earliest plastics were used to imitate natural materials, for example ivory, tortoiseshell,

In a way this enabled them to become part of people’s lives without causing too much outrage. Plastics were seen as luxury materials, but also democratic, opening up design and products to a wider audience.

To substitute a material successfully, plastics needed to not only resemble the other material but be convincing enough to the consumer that it would fit into their lifestyle. There is a deception involved, some of this deception is generated through the skeuomorphic capabilities employed in the design of plastics objects. The skeuomorph being ‘an object or feature which imitates the design of a similar artefact made from another material.’

The skeuomorphic object or feature is not necessary in the substitute material but reflects how the original material was used. This 1980s ice bucket is a perfect example of the designers use of skeuomorphs.

It is in the shape of a coopered barrel and is a promotional piece for a Perry drink. The staves of the barrel have graining marks just like the wood it is imitating, and the metal hoops look like they have been riveted in place. Of course, the whole object has been moulded out of a single material, in one piece, but it reflects the original design in great detail. A significant amount of work has gone into the creation of this piece, all of which was completely unnecessary but make for a more interesting and appealing object than a plain brown bucket.

Substitute materials can appear very good from a distance but betray themselves at close quarters. Early synthetic materials and processes, unlike later examples such as the ice bucket above, could not offer the naturalistic patterning of woods and other materials. Inherently lightweight plastics are not able to offer the physical weight of the authentic material, highlighting the deception when they are picked up.

The 1930s Roanoid ashtray below has a metal weight in the base enabling it to resemble marble both in feel as well as visually. I was able to use it to play a trick on some students who came into the museum. I was talking to them about materials, and I asked them to think about what a number of objects were made of. When a materially perceptive, modelmaking student picked up the ashtray he knew it would be made of some kind of plastics material and expected it to be light weight. When it was heavy the confusion on his face was perfect.

If we look again at the 313, see above, the skeuomorphic effects are not as obvious as the examples I have just shown, it doesn’t have the wooden texture or strong patterning, something that was probably hard to achieve at the time, but the fancy detailing at the bottom could be seen as being carved if it were made of wood.

What this case does do is hold the consumers hand, and help them to come to terms with the unknown, the future. It opens the doors to the Modern world.

In contrast to the earliest plastics material usage, some designers and manufacturers were keen that plastics were allowed to do what they were capable of, not just resemble something else, but to be used to their fullest potential.

Chermayeff’s design on the right, from 1933, still has a resemblance of the furniture style, it is still quite boxy despite the rounded corners, however the radio at the bottom, from 1935, feels more Modernist and makes me think of a car dashboard.

Wells Coates pushes the boundaries of radio case design with the AD65, designed in 1932 but manufactured in 1934, the first of the round radios, it could not have been made of wood, it exploits the material’s capabilities. The round shape is designed around the speaker which sits in the centre, and has a touch car radiator grille with the chromium plating over the speaker.

However, due to the technology that they contain, these radios are still

large pieces. The innovative and

forward-looking designs were still pieces of furniture – they could be mounted

on stands to elevate them. This

elevation also makes them look like sculptures on plinths, showing off the

beauty of the radios not hiding them away.

EK Cole were known for some great innovations in radio design but I think one of the best has to be in helping the ordinary housewife of the 1930s find the radio stations they had trouble finding on the fiddly dials!

Louise Dennis, Curator of MoDiP