|

Image

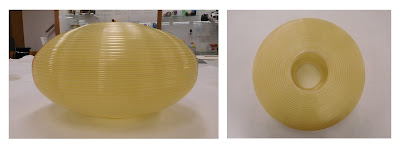

ref: The small lampshade, AIBDC :

008834 Image credit: Katherine Pell |

We believe it to be part of a floor/table lamp as opposed to a ceiling pendant, although the original attachments are missing – refer image below for a similar, complete example.

|

Image

ref: What we think our shade might have looked like with a wooden stand. Image credit: https://keup.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/rotaflex-31.jpg |

It is very similar to another shade we have, designed by John and Sylvia Reid for Rotaflex in spun cellulose acetate.

|

Image ref: Rotaflex large

ceiling pendant, AIBDC : 000870 Image credit: MoDiP |

The manufacturing method was patented in 1946 by Danish civil engineers Bent Højberg- Pedersen and Bent Panker. It involved first extruding the cellulose acetate plastics material through a nozzle, to create a filament with a circular cross-section. This was then helically wound around a wooden former of the desired shape, with some form of adhesion then applied to adjoin the neighbouring filaments together, such as brushing/spraying with a solvent. Two filaments could be laid down simultaneously, which seems possible for both of MoDiP’s examples as they each possess alternate layers of transparent and opaque strands. This would have produced a decorative effect in use as each layer would display a different degree of light transmission.

|

Image ref: A Rotaflex shade being made at a factory

in Australia, 1967. |

It became known as the rotaflex process and was licensed out to other manufacturers by Pedersen and Panker before they set up their own company several years later, also called Rotaflex. To further confuse matters, the Rotaflex (with a small or capital ‘r’) name was often used to brand the shades designed by these different manufacturers, some choosing to adopt the name for their own lighting companies as well!

|

Image ref: Six of the shades

in this Disderot display in 1955 feature A.R.P. rotaflex designs. Image credit: https://postwarbritish.co.uk/disderot-rotaflex-france/ |

Around the same time, a British lighting company was established by Bernard Stern named Rotaflex (GB) Ltd, that not only made original designs but also manufactured and distributed some of the Disderot/A.R.P. rotaflex shades. It was Stern who commissioned John and Sylvia Reed who subsequently went on to add two of their designs to the Disderot catalogue in 1957.

|

Image

ref: The ‘Metallux’ range designed by John and Sylvia Reed for Rotaflex GB, 1957. Image credit: https://keup.wordpress.com/2019/08/11/rotaflex/ |

Other companies were then set up in the US, Australia and across Europe, all of them interconnected, creating their own Rotaflex shades as well as selling each other’s designs. Unfortunately, the shades are rarely marked with the maker’s details but production was prolific throughout the 1950s and 1960s, stopping by the 1970s as the technique fell out of fashion.

|

|

If you would like to find out more on the subject, check out the amazing post war british website that features original interviews, archive photographs, exhibition catalogues, promotional advertisements and more.

|

|

Katherine Pell

Collections Officer

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1223428/po200-lampshade-reid-john/

https://keup.wordpress.com/2019/08/11/rotaflex/

https://patents.google.com/patent/GB753655A/en?

q=rotaflex+cellulose+acetate+lampshades&oq=rotaflex+cellulose+acetate+lampshades

https://postwarbritish.co.uk/tag/rotaflex/

https://www.design-mkt.com/162790-vintage-rotaflex-pendant-lamp-sweden-1960s.html

https://www.instagram.com/p/BtzS1n5nlvnYvL21XGQkZhBXZtXsh675KMDkNc0/

https://www.johnandsylviareid.com/

https://www.perfiner.dk/lyngby-naerum-jernbanemaerke-fundet-med-perfinbilledet-rx-r-27/

https://www-vintagedesignlighting-com.translate.goog/heifetz-rotaflex.html?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-GB&_x_tr_pto=nui,sc