The 2022 Tour of Britain bike race takes place from 4th - 11th September, with Stage Seven seeing the riders pass through MoDiP’s local area. In anticipation and in celebration of this exciting event, we have put together a pop-up exhibition exploring the increasing role of plastics within the cycling industry.

Here are some of my favourite objects:

|

Image

ref: The San Marco REGALe saddle on display. |

The REGALe racing bike saddle, manufactured by

Selle San Marco in 2012, was first introduced in 1984, then called The Regal. It

proved very successful amongst the professional racing community, in part due

to its weight but mainly because of its comfort. This successor, the REGALe (e

= evolution), retains the classic shape of the original but provided an

opportunity for the company to introduce more modern materials. Released in

2010, it features a carbon fibre base making the saddle even lighter than

before. We always enjoy putting this object

on display because viewed in profile, it reminds us of Concorde!

|

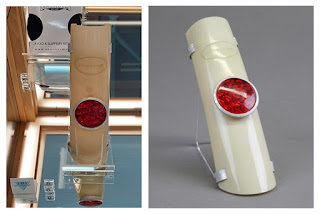

Image ref: A 1950s mudguard extension. Image credit: Katherine Pell/MoDiP |

This lovely object is a clip-on mudguard extension with a rear reflector, made of cream coloured, thermoformed, cellulose nitrate and dated to circa 1950s (although it may date earlier). It was featured as part of our 10 Most Wanted project through which we hoped to find out some more information, such as who designed it and which company manufactured it. All we know is that it was ‘British Made’ from moulding details on the front.

Rear

reflectors were made a legal requirement in 1927 and, in response to the

increasing number of road accidents, in 1934 the government introduced new

requirements for bicycles to improve their visibility at night by carrying a white 12 sq. inch panel as well. Contemporary images show rear bike mudguards often painted with a white tip so obviously people were aware that this was a good idea, even before the legislation came into force. Could this object be an enterprising manufacturer's safety accessory from around that time?

|

Image ref: The Rehook

on display and my mucky hands! Image credit: Katherine Pell |

The Rehook bicycle chain tool is designed to help cyclists get the chain back on to their bikes quickly, easily and without the mess of oil and dirt on hands and clothes. It is something I definitely needed the other day on my morning commute to work, when my bike chain came off – refer image above, on the right!! Designed by Wayne Taylor, it is made from glass-reinforced nylon, and has an adjustable high-grip silicone strap to attach the tool to the bike frame for easy accessibility. Weighing only 20g, the handle incorporates a honeycomb structure to assist with weight reduction and using plastics materials helped to keep production costs affordable, whilst providing strength, durability and a good range of colours for the tool. Rehook was pitched on the BBC programme Dragon's Den in 2021 successfully resulting in a £50,000 investment in return for a 25% share of the company.

|

Image

ref: The undershorts with a D3O insert on the right. Image credit: MoDiP |

Developed by British engineer

Richard Palmer in 1999, D3O is an innovative material with intelligent

molecules that protect against injury. The putty-like substance has

free-flowing molecules which lock on impact, absorbing and dispersing energy before

instantly returning to their flexible state. Here, D3O is used to provide

impact protection at the hip in the Race Face cycling shorts.

It has been moulded to shape and is held in place in strategically located

pockets so that it can be removed prior to washing.

Also on display is a carbon fibre composite road bike wheel, a fold-your-own polypropylene sheet mudguard, a stretch silicone LED light, and knee/shin pads with Kevlar®: a variety of synthetic materials that assist cyclists in staying aerodynamic, comfortable and safe.

Re: cycling will be on display until 12th September 2022, on the first floor of the AUB Library.

Katherine Pell

Collections Officer